1. What prompted the decision to digitally print and temper the centre of the Ghost table’s glass top—and how does that material intervention support long-term durability and aesthetic permanence?

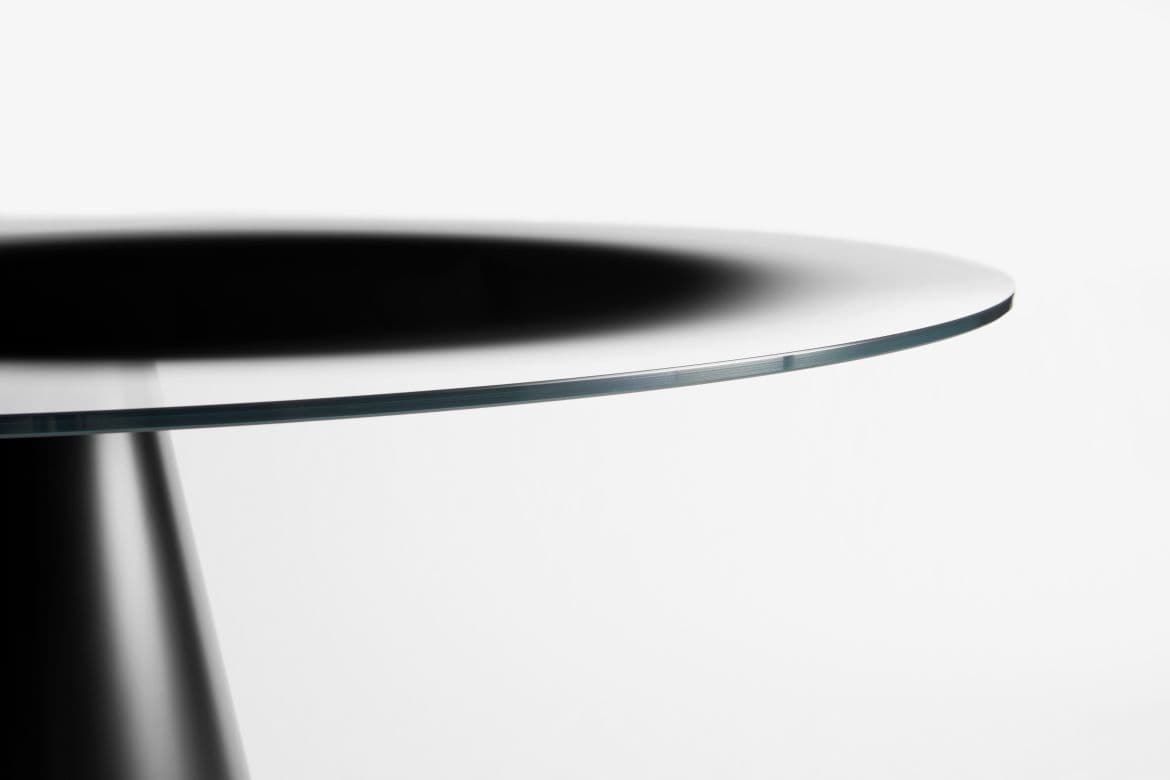

I started with the idea of using digital printing to visually reduce the surface of the glass top. This technique is typically employed to apply decorative patterns or textures, but I wanted to take it in a different direction—more conceptual and unconventional. My aim was to make the table appear more compact and lightweight than it actually is, subtly altering the viewer’s perception of the object.

The black digital print, designed with a delicate gradient that fades toward the edges, interacts with the glass’s transparency to create a refined perceptual effect — an emergent quality that goes beyond the visual, reshaping the spatial reading of the object. This contributes to a sense of visual lightness and harmony with its surroundings.

The print is applied before tempering, permanently fusing with the glass. This process ensures superior resistance to wear, scratches, and UV exposure, and guarantees that the visual effect remains unchanged over time. In this way, the technique becomes both expressive and functional. It reflects my approach to rethinking materials and processes — not by adding, but by subtracting, embedding meaning directly into the material, both technically and perceptually.

2. The Ghost table’s removable metal base emphasises transportability—how did you approach joinery, finishes, and material selection to balance resilience with modularity?

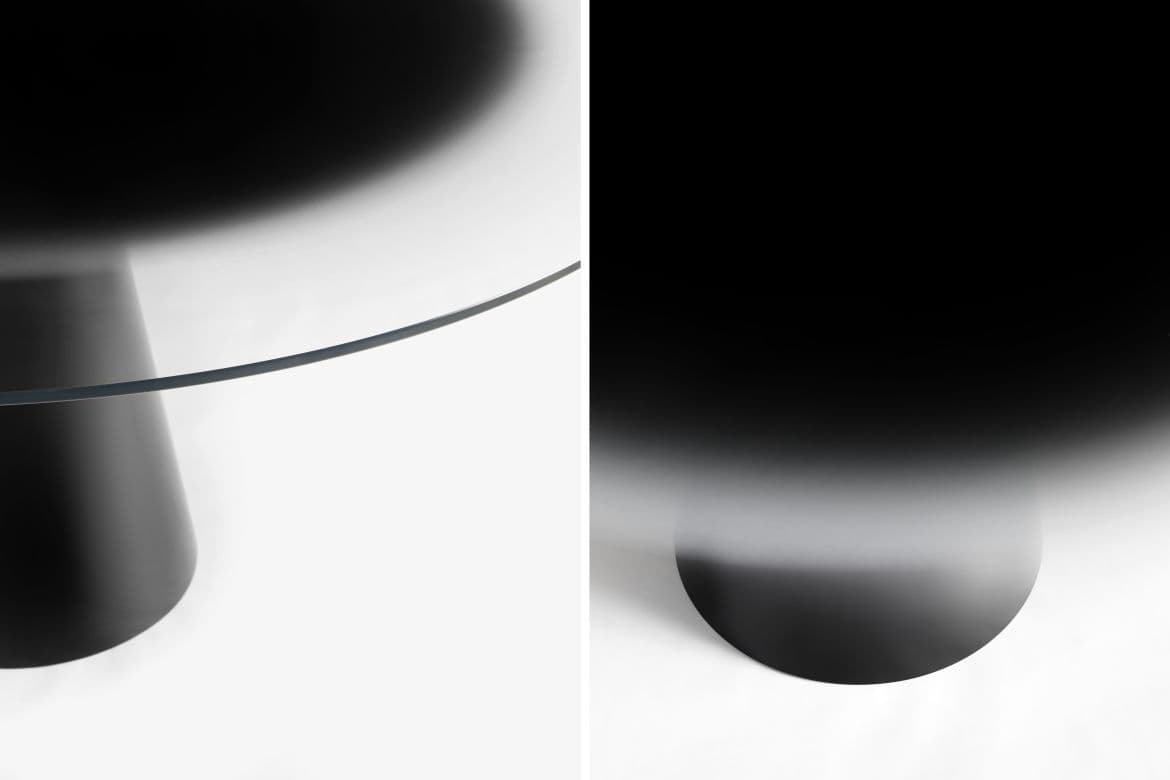

From the outset, I wanted the metal base of the Ghost table to be proportioned in relation to the printed section of the glass top, to preserve visual coherence and reinforce the perceptual effect. Achieving this required balancing form and stability, resolved through a system of modular weights that can be disassembled for easier transport without compromising structure.

The glass is secured via a steel plate designed for easy removal. The finish of the metal frame matches the colour of the glass print, allowing structure and surface to merge visually into a single, compact and continuous volume. The entire system is made of metal, selected for its strength-to-weight ratio, compact proportions, durability, and recyclability.

3. In Graffio’s metal cabinets, how did you control the abrasion patterning to retain narrative 'imperfections' without compromising surface integrity or accelerating corrosion?

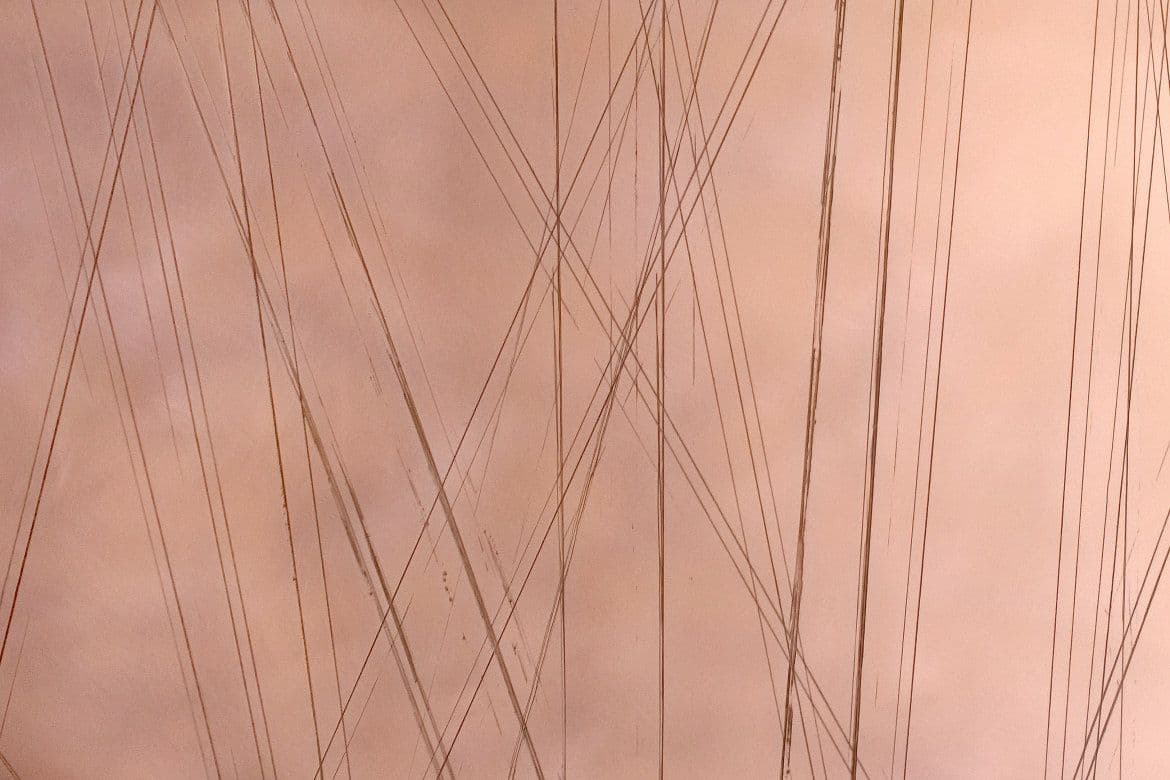

We employed a technique based on controlled metal erosion, allowing us to engrave deep, expressive marks into copper, brass, or steel. The process penetrates to a calibrated depth while preserving the metal’s structural integrity. After etching, a transparent protective finish is applied to enhance resistance to wear and oxidation, without affecting the surface’s tactile quality or raw appearance. The result is a surface that merges technical performance with aesthetic value — a texture that appears organic but is precisely engineered.

4. What properties of H10 DeErosion copper/brass made them well-suited for Benevelli’s etching techniques and for aging gracefully over time?

The H10 DeErosion copper/brass alloy offers a rare combination of structural purity and surface reactivity. Its controlled grain and low surface tension make it ideal for precise, expressive engraving, free from smudging or delamination. Its natural tendency to oxidise — even when protected — enhances the piece’s narrative rather than compromising it. This balance between technical performance and aesthetic evolution is central to my work.

5. Beyond aesthetics, how do the etched ‘scar’ lines in Graffio contribute to the piece’s functional performance, for example in wear-masking or tarnish resistance?

The etched lines hold conceptual weight: scratches are highlighted rather than hidden. We industrialise irregularity, transforming what would normally be rejected into a narrative and identity-defining element. Each surface becomes a sort of landscape — a map of controlled imperfections where the "flaw" becomes expressive language.

6. For Shelf, how did you evaluate porcelain stoneware’s structural properties to serve as a load-bearing horizontal surface—did it require reinforcement or special mounting strategies?

The Shelf project relies entirely on the structural solution of its assembly, allowing it to support over 150 kg — far beyond what’s typical for ceramic shelving. I personally engineered and tested the system. The porcelain stoneware used is a standard, mass-produced product with no internal reinforcements. The installation method is also key: it mounts like a regular tile, requiring no complex systems or hidden supports. This makes the shelf not only minimal and elegant, but also accessible and replicable. Shelf becomes an architectural element — a hybrid of furniture and cladding.

7. Could you walk us through the collaboration process with Coem during Shelf’s development—how did material constraints inspire innovative edge-folding or shelf-integration details?

The biggest challenge was convincing Coem the project was technically feasible. I chose to engineer the entire system myself, demonstrating its viability and structural solidity. Porcelain stoneware is rigid and fragile, so it doesn’t permit traditional bends. Instead of bending edges, I reimagined them as L-shaped structural elements. This reinterpretation turned a decorative slab into a self-supporting shelf — now one of the project’s defining features, both functionally and aesthetically.

8. All three projects emphasise lifecycle thinking—how does your studio integrate circularity early in material sourcing, prototyping, production, and end-of-life?

For me, durability is an ethical choice as much as a technical one. A well-conceived project should not have a defined "end". This principle informs all stages of my work. Circularity starts with material selection — considering durability, disassembly, reuse, or recyclability. I often prototype personally to test not just form and function, but also how materials evolve over time. In all three projects, materials were chosen to age well, be easily separated at end-of-life, and remain meaningful over time. True sustainability is about creating objects that endure: physically, culturally, and emotionally.

9. From a material performance standpoint, which technical challenges stood out most across these three projects—and how did you prototype or test to resolve them?

The main challenge was to push technical boundaries without resorting to predictable solutions. The material itself was rarely the starting point; the intention was to use it in an unconventional way. This required a design-driven prototyping process, where testing wasn’t just for validation but a form of exploration. What initially appeared as flaws — fragilities, deformations, irregularities — often became generative elements that helped redefine the project.

10. Your work with metals, glass, and ceramics spans multiple material families—how do you decide which material system best expresses an intended narrative, especially in sustainable design?

Material choice begins with narrative. I look for materials that embody the project’s story. Design, at its heart, is research and experimentation. Beyond symbolism, sustainability plays a guiding role. I assess each material's life cycle — sourcing, processing, durability, end-of-life. The ideal material fits within a circular framework, ideally with no "expiration".In the end, it’s a balance between poetic meaning and technical feasibility — narrative strength aligned with environmental responsibility.

11. How are you exploring new bio-based or reclaimed materials to evolve this material-driven, sustainable design narrative in future projects?

I’m deeply involved in researching bio-based and regenerated materials. For me, it’s vital to understand a material’s origin, transformation, and post-use journey. I’m especially interested in partnering with suppliers who develop low-impact materials that still meet aesthetic and performance expectations. Regenerated or upcycled materials are also key, helping to reimagine production cycles. It's not only about "green" materials. It's about creating objects that narrate responsibility and care.