What sparked the inspiration for the design of Pago lighting, and the use of discarded materials like oyster shells?

South Korea is the world's second-largest producer of oysters, following China. Producing around 300,000 tons annually, it generates a market worth close to 300 billion won (as of 2022).

According to the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries of South Korea, out of the 360,000 tons of shell waste produced annually, 80%, totalling 290,000 tons, comprises oyster shells. Consequently, up until last year, around 180,000 tons of oyster shells were disposed of at sea or buried on land annually. The remaining 110,000 tons are used as a substitute for limestone in power plants and steel mills.

While there are methods such as burning and crushing oyster shells for use as fertiliser on farms, farmers have turned away due to the remaining salt content. The carbon dioxide and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted during oyster shell incineration are also additional pollutants in the era of the climate crisis. Ultimately, oyster shell disposal remains one of the unresolved 'challenges' in Korean society.

Pago is produced by mixing oyster shells with 50%. Through this, we aimed to effectively address the issue of oyster shell disposal and discover the potential for using it as an alternative material in the design industry with new textures and aesthetics.

I have a consistent interest in things that are discarded. My sculptural grammar is about connecting and stacking things that are consistently discarded. Through this, we can create connections between discarded and seemingly meaningless things. I believe that connectivity is a means we need in our journey to find the meaning of 'existence' and 'being alive.'

Pago resembles a Buddhist pagoda in its form. It can exist individually but can also be stacked together to constantly rise. Through this form, we aimed to express a wish for the connection of discarded existences.

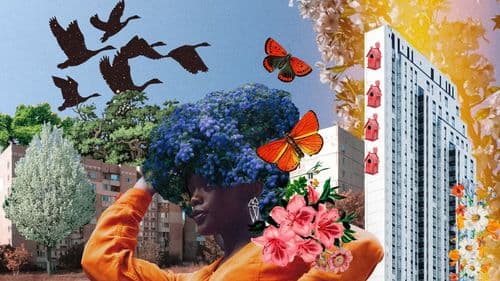

Can you elaborate on the non-human-centred approach taken in the NOYST project, particularly how it aims to expand urban biodiversity?

Non-human-centered design is not a formal concept. However, defining, it can be considered as a design that regards the interdependent relationship between humans and non-humans, setting the non-human as the subject of production, use, and disposal. Non-humans encompass a wide range from living organisms to objects and the environment. It is typically developed through interdisciplinary research, particularly closely associated with ecology.

In the context of promoting biodiversity, urban green spaces are presented as opportunities. The IFLA (International Federation of Landscape Architects) and the ZSL (Zoological Society of London) have suggested parks as spaces for the conservation of urban wildlife. Additionally, Paris has implemented a "Biodiversity Plan" to integrate biodiversity enhancement into urban planning by 2024.

Against this backdrop, I conducted research to identify the species most at risk and their needs among the organisms living in urban parks. The subject of the project is the chickadee, a common bird species in Korean urban parks. It is also a climate change indicator species and has the greatest impact on bird richness, playing an important role in controlling pests and influencing the health of ecosystems and urban biodiversity. However, the population of chickadees in urban parks has been significantly declining, leading Seoul to designate chickadees as a protected species in 2017.

Chickadees nest in hole nests, but they cannot create nesting holes themselves, leading to a high reliance on artificial structures, which increases their vulnerability to risks such as friction with humans or exposure to predators. Conversely, there is a high probability that these artificial structures will be utilised by chickadees, making them suitable targets for this project.

Therefore, through NOYST, I decided to design safe birdhouses for chickadees, enabling them to breed and survive, thus contributing to increasing their population and biodiversity.

Can you walk us through the material and design choices in NOYST?

NOYST is a birdhouse designed specifically for chickadees, made by mixing oyster shells and natural resin pine sap. Oyster shells, as mentioned earlier, are a material that needs to be reused due to various problems such as marine debris.

Additionally, the main component of oyster shells, calcium carbonate, has the effect of improving soil quality. The purpose of NOYST is to convert sea garbage into land fertiliser for circulation. Through this, it helps plants, which serve as habitats and food resources for urban wildlife, to grow well.

According to the study by Joo, and Eun-Jin (2017), the form of artificial nests with an entrance diameter of about 5.5cm and a passage of about 5cm was found to have the highest breeding rate for small birds. This form is chosen because it has high accessibility due to its large entrance diameter and is relatively safe from threats of predators as it requires passing through a 5cm passage. In this project, to avoid competition with other species, an entrance diameter of 3-3.5cm, suitable for chickadees, was selected.

Furthermore, artificial birdhouses often have anthropocentric forms and functions. Most of them resemble one-dimensional box-shaped 'houses' and are designed for humans to observe/research birds. Also, accessories like nails can interfere with the growth of trees.

Therefore, I aimed to design a birdhouse specifically for chickadees in a more organic form that harmonises with nature.

Accessories connecting wood and nests are modular assemblies using cable ties and rivets, making installation easy and contributing to sustainability by allowing reuse and repair without using adhesives.

Amazing. Let’s talk about another urban-related project - the Tiny Houses Project. How did you approach the challenge of maximising space and integrating natural elements in limited square footage?

Tiny House is a project to design a compact home on a 42㎡ plot near a park in Gwanak-gu, Seoul. Gwanak-gu is an area with a very high population density, with approximately 160,000 people per square kilometre. I lived in this area for three years, and due to the high population density, the houses were tightly packed together, and there was hardly any view of nature outside the windows. Experiencing the ever-changing nature a little bit every day is essential for enhancing the quality of life.

The plot for the tiny house faces a walking path to the south and is surrounded by forest on the other three sides. In other words, one side is closely connected to humanity, while the other sides are closely connected to nature.

The walking path has a lot of foot traffic. Rather than making the first-floor closed-off, I wanted to create an open space like a café or gallery to generate revenue effectively while fundamentally creating a welcoming image for the building.

And importantly, there are variable and small boundaries. The café on the first floor has low windows that connect to the private garden behind the building, which is then connected to the semi-basement office. The windows on the semi-basement office serve as ventilation and lighting while allowing views of nature, connecting the small spaces. This not only helps reduce energy consumption but also enhances the well-being of the residents.

The second and third floors are living spaces for the users. Windows are placed allowing views of nature and sunlight from the three sides. Especially, the west side has full-length windows so that residents can enjoy changing views while climbing the stairs. As you go up, the space becomes more private, and the size of the windows decreases, increasing insulation.

Half of the rooftop is used as a multipurpose room, and the other half is designed as a private space for outdoor activities while looking at the sky.

Could you discuss the considerations involved in selecting materials and designs that both address environmental concerns and meet the aesthetic and functional needs of your projects?

I consider various factors such as material sustainability, eco-friendliness throughout production and disposal processes, and recyclability to address environmental issues through design. However, often due to functional and practical reasons, I have to prioritise these factors or compromise on some.

The term 'eco-friendly' encompasses many aspects, making me particularly sensitive to its usage. Strictly speaking, my work, PAGO, may not be entirely eco-friendly. However, in this project, I aimed to address two main issues. The first is reducing carbon emissions during material transportation. The second is exploring new possibilities by discovering new aesthetic elements to utilise socially problematic waste materials as resources. I constantly consider which issues to focus on and what areas may be lacking.

Furthermore, albeit sounding somewhat unusual, NOYST prioritised harmony. Just as it is natural for trees to be in forests both functionally and aesthetically, we placed materials in places where their colours and forms can best serve their functions, ensuring that what comes from nature can return to nature.

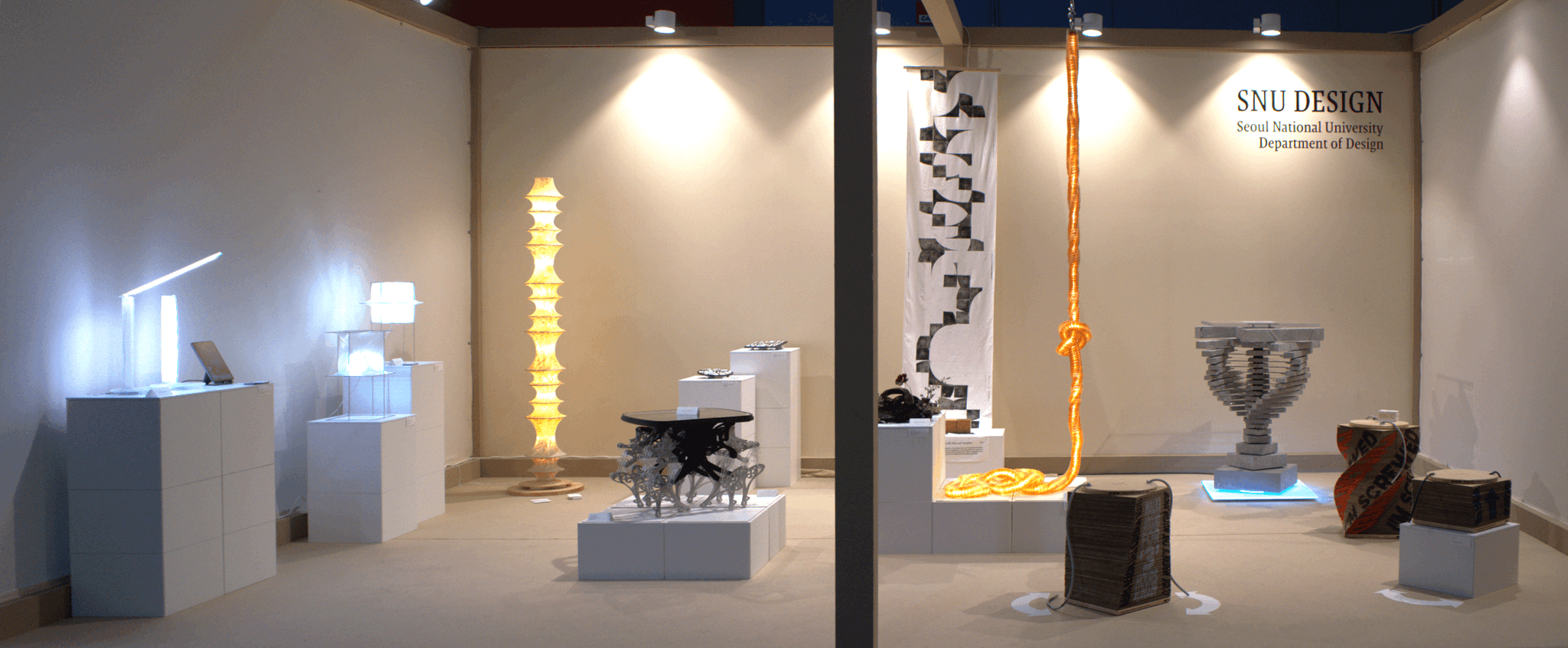

Reflecting on your participation at Milan Design Week 2024 where you showcased PAGO, how has the exposure to international design trends and feedback influenced your future design projects and approach to sustainability?

The Milan Design Week 2024 featured many fascinating works. I was inspired by the experimental projects from various design schools.

When working with natural materials, it's essential to fully understand the characteristics of the materials and to experiment with mixing various substances. I believe that finding forms that align with the properties of the materials and the methods of production is the right direction.

Additionally, using eco-friendly materials alone may not be a sufficient solution for sustainability. Viewing objects as living entities and considering their life cycles can lead to sustainable design when used flexibly. Projects like Forma Fantasma's 'Ore Streams' from 2017 or Yuxuan Huang's work reconstructing old cabinets could serve as excellent examples of this.

Looking forward, what are the key areas of material innovation or sustainability you are interested in exploring through your future projects?

I want to pose questions about the lifecycle of products in future design projects.

Due to the logic of economics, we often create products that are inexpensive and durable, leading to the production of seemingly permanent items. However, considering that our actual usage period is often much shorter than the product's entire lifecycle, I believe it is necessary to address this discrepancy. Perhaps, aligning the duration of our usage with the product's lifecycle could be a consideration.

I'm personally drawn to natural materials and foresee continued use of them. However, in the process of addressing the inherent durability issues of natural materials, we may inadvertently extend the lifespan of products. This raises concerns about whether we might be disrupting the natural lifecycle of these materials. Could we potentially accept disposal as part of the product experience? For instance, imagine creating outdoor party chairs made from cookies, which could eventually become food for ants, allowing them to join the party as well.

Additionally, I aim to explore materials specific to particular locations, such as clam shells. This pursuit serves not only to reduce carbon footprints during transportation but also to create interesting contexts intertwined with various local elements like history, culture, and religion.