1. The FL50 floor lamps use reclaimed natural stone as their main material. Can you explain how this choice of material was translated into your design process?

Reclaimed natural stone has been central to my design practice from the start. I’ve always approached it with a set of guiding principles, particularly questioning its value and function in contemporary design. A key part of this is leaving the stone as untouched as possible. This might seem anti-design, but it stems from my belief that intervention often doesn’t enhance the material — its beauty is already inherent.

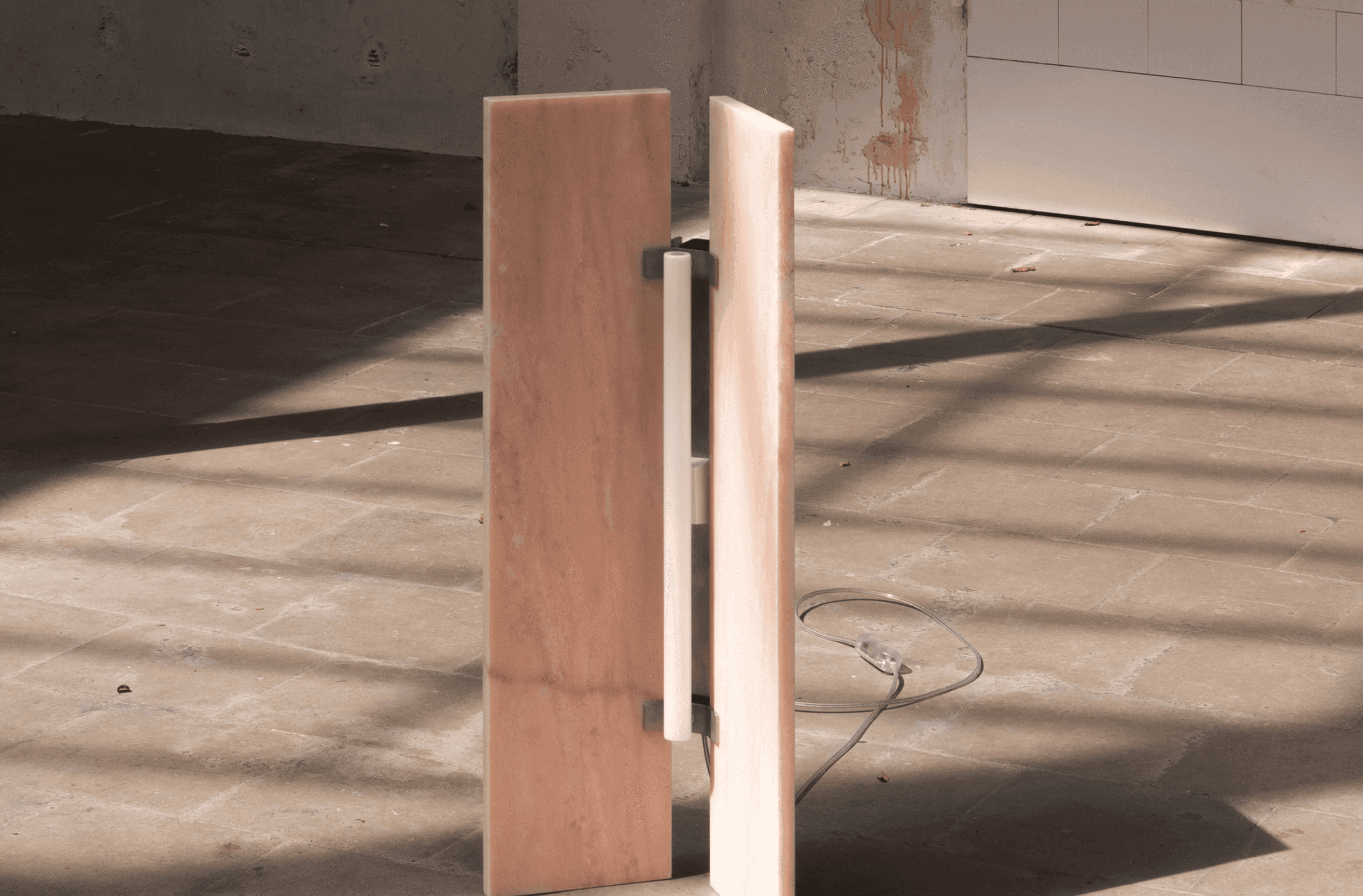

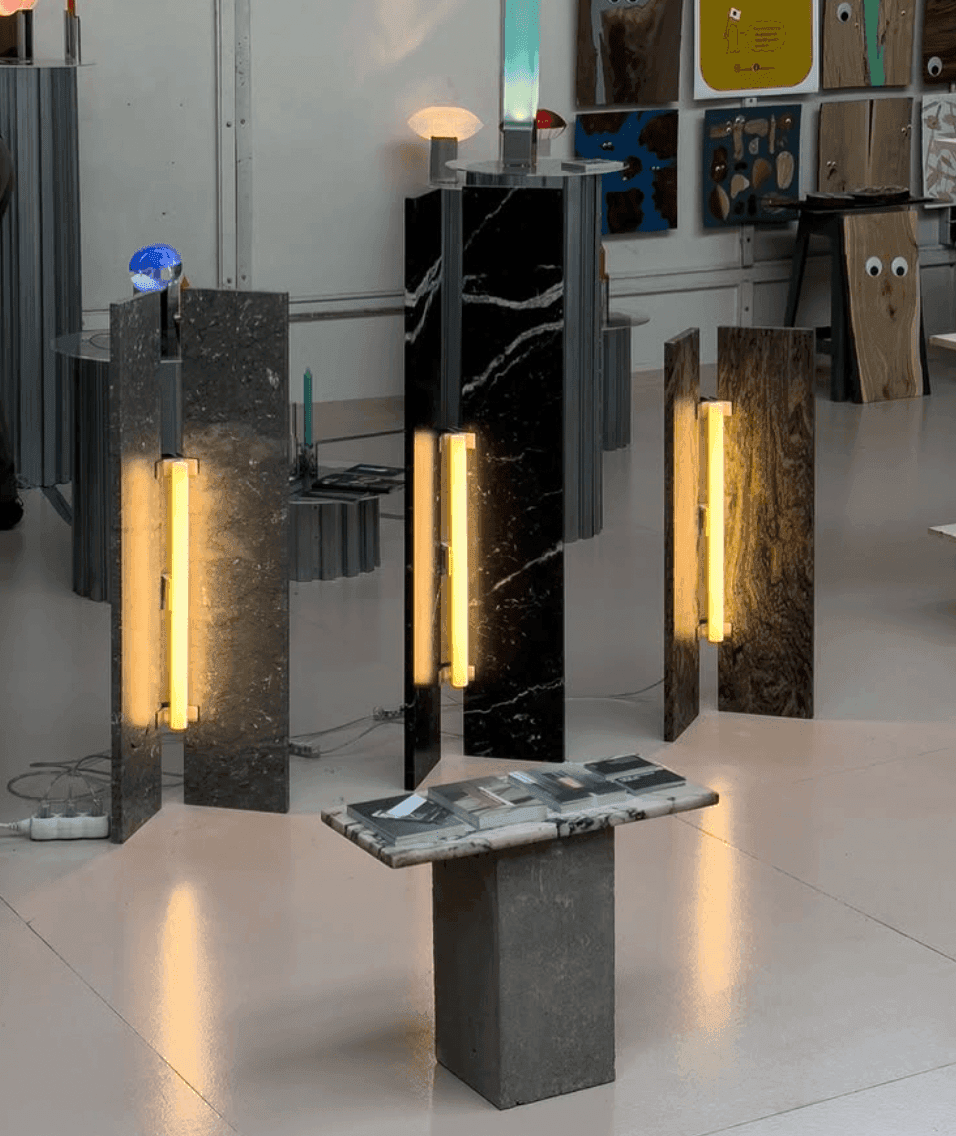

With the FL50 lamps, I wanted to contrast the stones' past lives — typically used as cladding — by placing them upright and allowing them to carry the structure, rather than being carried by it. This inversion was both aesthetic and structural. Because of the weight of both the stone and stainless steel elements, setting the stones at a 90° angle opposite each other created a stable base. The same brackets used to hold this angle also connect the stones to the rest of the structure, keeping the design simple and efficient.

2. What specific challenges did you face in sourcing and working with these reclaimed materials, and how did you overcome them to ensure their functionality and beauty?

Many of the stones I used had already been removed from their original contexts, allowing me to assess their condition from photos. Most had superficial damage — scratches or leftover glue and mortar — but I avoided stones with structural cracks. Logistically, sourcing was the most time-consuming part: I drove all over Belgium to personally inspect and select stones. Fortunately, their relatively low cost helped offset the time and fuel involved.

In other cases, I dismantled intact elements like mantelpieces and windowsills. This required deciding whether to commit before seeing the stones as separate pieces. With help from friends, I learned to carefully take these apart while trying to preserve as much material as possible. These experiences deepened my empathy for the materials, which is central to my practice.

3. Could you walk us through the technical reasoning behind using stainless-steel brackets instead of glue or screws, and how it contributes to the lamp’s sustainability and reusability?

Working from an existing connector by Hitch Tools, we developed a custom bracket system that uses only two screws to secure the stones without damaging them — no drilling, no glue, no cutting. Just the tension of one screw at the top and one at the bottom holds everything in place. This approach preserves the stone’s integrity, allowing it to remain a non-specific part that could serve future purposes.

The brackets include spacers to accommodate different material thicknesses, allowing users to replace the stones with glass, metal, or wood panels — even found materials — with no adhesives required. Additionally, the brackets attach to the lamp’s main steel tube via threaded holes, making it easy to disassemble, swap parts, or even repurpose the object. This modularity ensures a longer product life cycle.

4. What role does the concept of ‘upcycling’ play in the FL50 floor lamps, and how does it differ from traditional recycling in terms of material integrity and longevity?

I’ve never felt strongly aligned with the term ‘upcycling’ in its typical sense — altering waste materials to give them new functions. My practice leans more toward restoration and re-contextualisation than transformation. I aim to preserve a material’s original character and let it speak for itself in a new context.

That said, the FL50 lamps are the first time I’ve allowed myself to cut the stone to a size of my choosing. Still, the philosophy remains: I use materials respectfully and with minimal intervention. This ensures material integrity, supports longevity, and enables future reuse without further processing.

5. Could you explain the process of preparing the reclaimed marble and granite for the FL50 lamps?

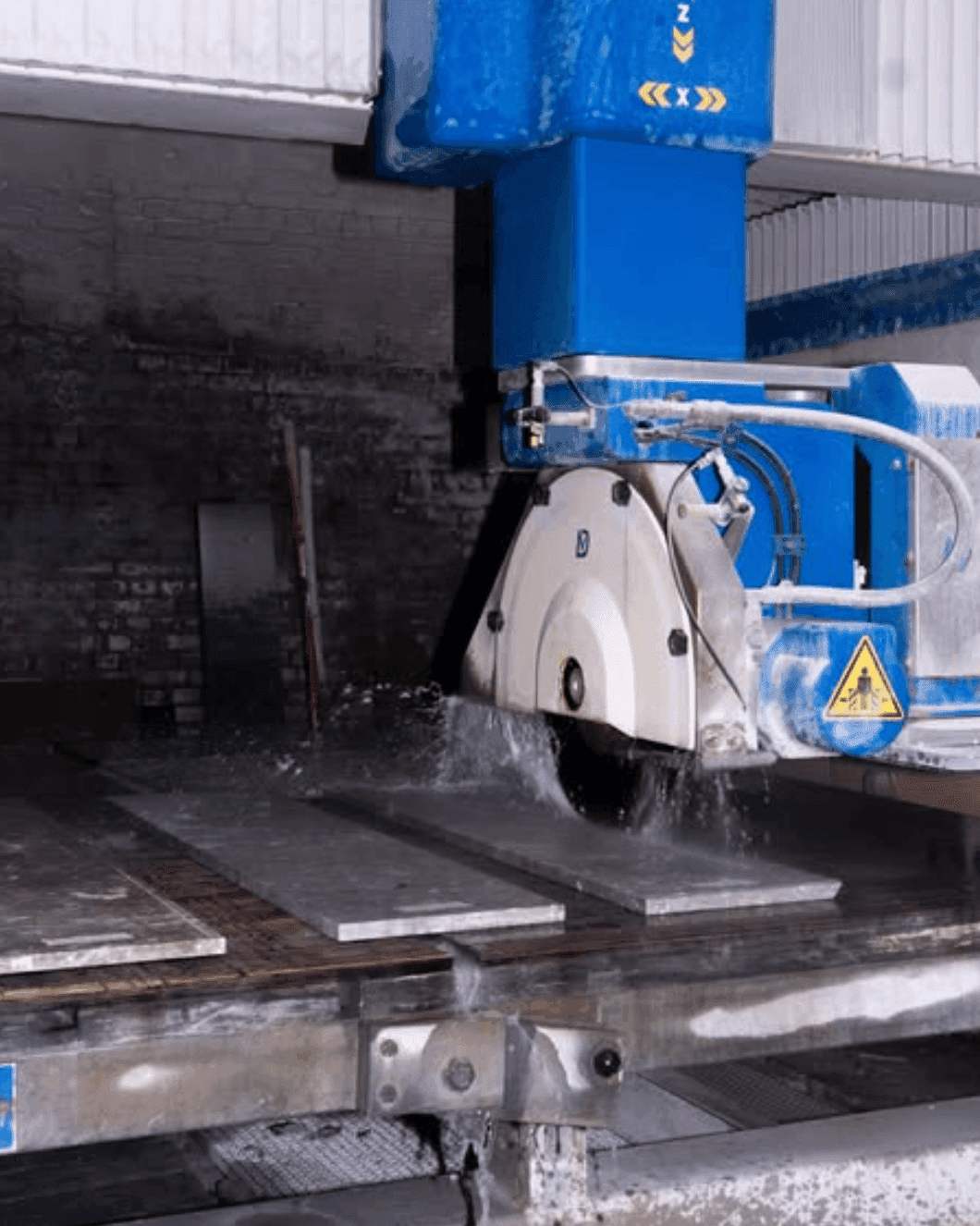

From the reclaimed stones I gathered, I standardized three sizes — 20 x 82 cm, 20 x 98 cm, and 20 x 114 cm — to minimize offcuts while maintaining control over proportions. After cutting, each stone was sanded on both sides: the back to remove mortar/glue, and the front to eliminate scratches and damage. Edges were lightly beveled to reduce fragility, and all surfaces were honed for an even, tactile finish.

Stone thickness was critical. Most pieces were around 20 mm thick; I ensured they never dropped below 16 mm after sanding to maintain structural strength. Heavier stones also contributed to the lamp’s stability.

6. How did you ensure the design allowed for easy disassembly and reusability, and what impact does this have on the lamp’s lifecycle?

As noted earlier, every component in the FL50 lamp is designed for easy disassembly and reuse. The brackets, spacers, and steel tube create a modular system in which each part can be reused independently. This flexibility turns the lamp into a platform for change, rather than a fixed object — allowing it to adapt without compromising function or beauty.

7. How do you hope the FL50 lamps will alter consumers’ perceptions of waste and reclaimed materials in high-end design?

I treat each piece of stone almost like a person — with respect for its history, beauty, and potential. This contrasts with much of luxury design, where materials are often used to signify status rather than valued for what they are.

My earlier series, A Sanctuary for Salvaged Stones, was a first attempt to challenge that — doing as little as possible to fetishized materials and letting them exist outside of decorative excess. I want people to see objects as companions, not commodities. Yes, these lamps aren’t cheap, but their value lies in ethics and thoughtfulness, not extravagance.

8. How do you envision the future of reclaimed natural stone in design? Could this approach influence industrial manufacturing?

There’s a growing interest in reclaimed stone — some designers use raw, irregular fragments, while others (like myself) prefer controlled formats. These projects yield unique pieces shaped by material availability, making large-scale replication difficult.

Still, they offer a valuable mindset: materials aren’t just inputs, but active participants in design. In industrial manufacturing, this often gets lost. Mass-produced objects typically use smaller, standardized fragments, sidelining material uniqueness. That said, even these approaches serve the circular economy by efficiently reducing material waste.

9. How does your raw-material-focused approach reflect your broader design philosophy?

As mentioned, I want to shift the narrative around materials labeled as waste. My goal is to show their philosophical and aesthetic beauty. If people begin to value what already exists — rather than chase novelty — then design becomes an act of care, not just consumption.

10. What impact do you hope the FL50 lamps will have on consumers' understanding of sustainability in design?

While this echoes earlier points, I’d add: I hope the FL50 lamps show that materials from a previous life can retain or even gain beauty. Scratches, marks, and wear don’t lessen their value.

The design supports circularity — no glue, no permanent fixings — meaning the lamp can evolve with its owner or become something entirely new. That kind of adaptability is vital if we want truly sustainable design to take root.