What are the key biotechnological paradigms that have significantly influenced your approach to sustainable architecture and design?

Biotechnology and synthetic biology influenced a lot my approach to architecture and design, having a great impact also on my PhD pathway as they opened my research to new exciting and unconventional possibilities.

While promoting convergence between apparently “distant” disciplines, a biotechnological perspective on architecture and design can allow for the recognition of agency within construction materials, thanks to the direct incorporation of biological sources, living or engineered organisms, such as mycelium, microalgae, bacteria and protocells.

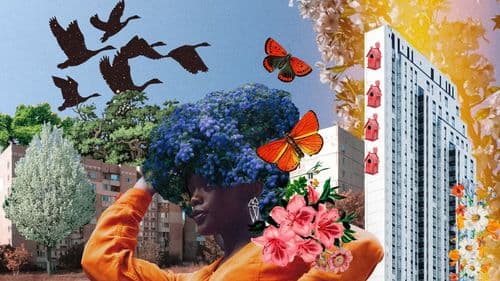

Through the integration of knowledge from different disciplines, this approach can in fact transform the traditional architectural and design practices into a broader vision, challenging the ontological separation between artificial and natural, human and non-human worlds. Specifically, I identify “bio-informed architecture” as an emerging design approach and transdisciplinary practice that helps acknowledge the intricate relationships between different species cohabiting within the built environment, while also increasing the overall sustainability of this sector.

Moreover, my approach to sustainable architecture and design is also highly influenced by posthumanism and material feminism (paying tribute to philosophers such as Donna Haraway, Rosi Braidotti, and Stacy Alaimo among others), since the objective of my research is to also redefine architecture as a place of co-existence between human and non-human inhabitants.

Architecture, as a designed construct, interacts with pre-existing conditions that are always the result of relationships with non-human entities already inhabiting that context. As a matter of fact, humans are constantly entangled with the non-human species, and it is, therefore, crucial for an architect or a designer to be aware of all these considerations when engaging with the context. The latter is never a void to be just anthropocentrically colonized or exploited. Rather, it is already full of intraspecific relationships that should be enhanced and valorised through a more conscious design.

Given your extensive research into biomaterials, what are the most promising biofabricated materials you believe will revolutionise sustainable architecture and design practices?

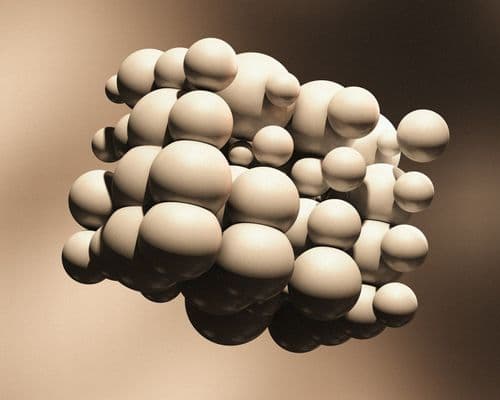

In some of my recent applications, I developed a series of prototypes aiming at fostering the debate around biological residues that we produce as food consumers, to be used as potential raw material to produce bio-tiles. The prototypes I developed in 2022 with this concept are “Shells-based bio-tiles”. In this case, I used eggshells, but also walnut shells, which are rich in lignin.

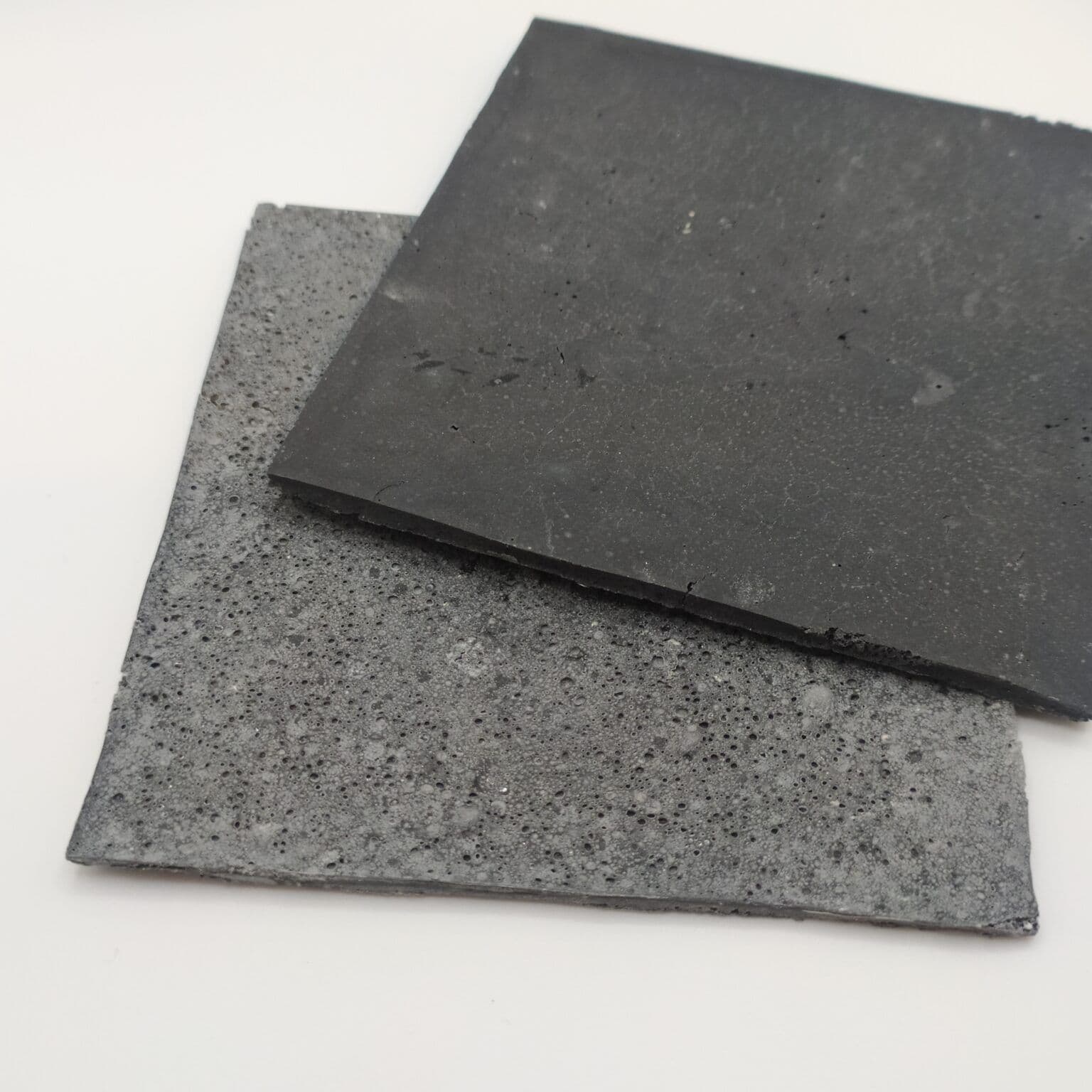

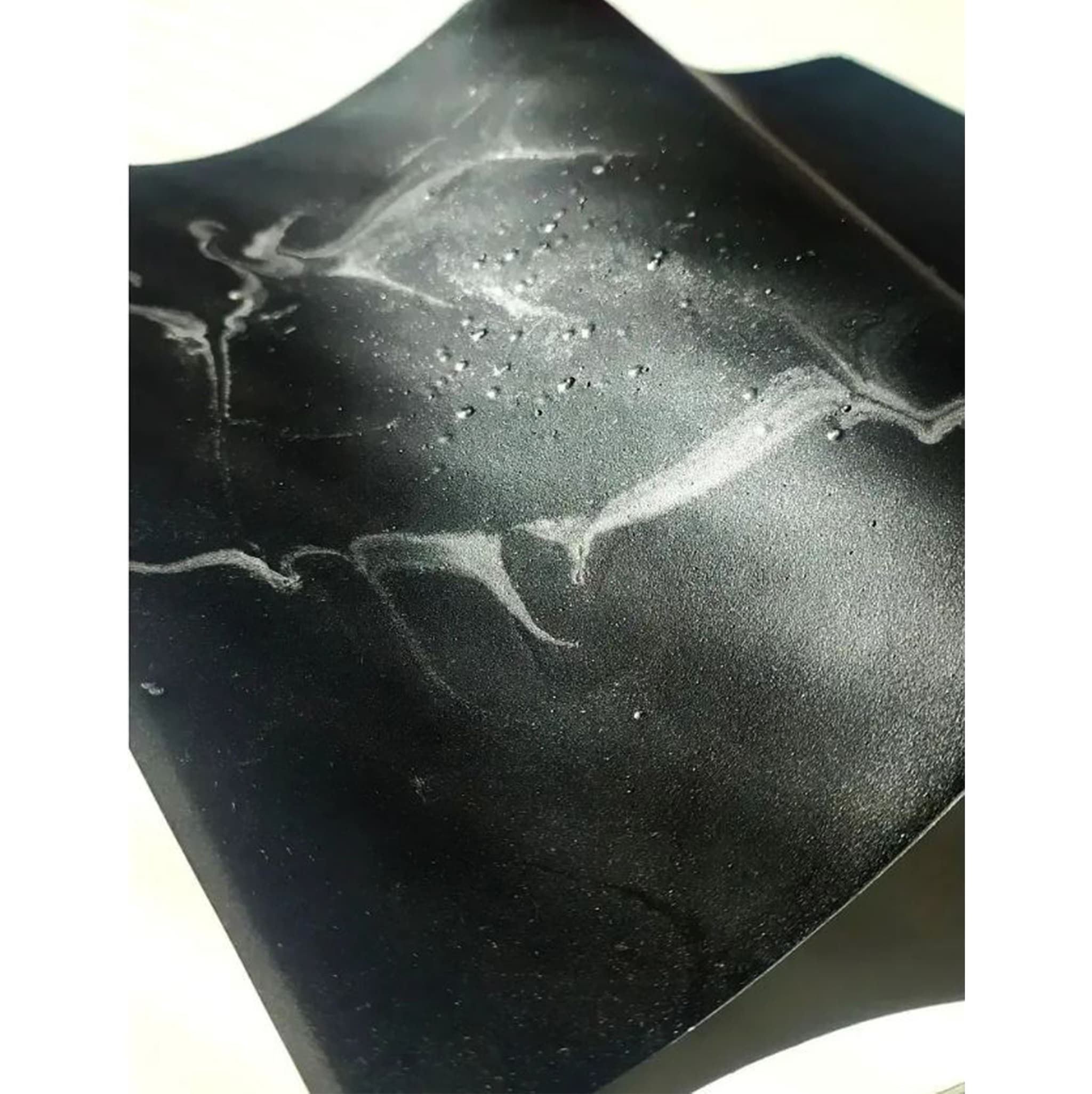

Among the samples I produced, I believe the most promising ones are the bio-tiles I fabricated using eggshells. These latter are composed of more than 90% calcium carbonate, which is the main chemical component of cement-based materials. Therefore, they can be used as substitutes in building materials or design applications. This process would reduce extractions, fostering the reconfiguration of the relationship between design and nature in an eco-syntonic way. For example, “NextNature Brick” is a series of bio-tiles composed of eggshell powder with the addition of blue and green spirulina and activated charcoal to create a marble effect on the surface. These samples aim to encourage the development of innovative production models, inspiring new aesthetics and triggering new considerations on the concept of living in bio-informed spaces made of food waste.

Following the same concept, I am currently experimenting with mussel shells which also provide a great quantity of calcium carbonate.

How do you envision the role of biotechnology and biomaterials evolving in the next decade within the context of sustainable architecture and the broader design industry?

Traditionally, the building sector produces an incredible amount of waste which has a permanent character and compromises the biosphere balance. In this context, bio-based materials, as an alternative to traditional building materials, can play a key role in stimulating a debate around the concept of dwelling, by promoting spaces that are the result of the combination of human and non-human agencies. Architecture thus turns into a medium that supports biodiversity rather than compromises it, reinforcing our ecologic relationship with otherness.

A direct consequence is also a more careful consideration of the entire lifecycle of the biomaterials deployed, ensuring end-of-life solutions that are less impactful toward ecosystems.

For all these reasons, I work between functional and more speculative projects to raise awareness and promote bio-informed designed spaces as potential supporting interfaces for a multispecies coexistence.

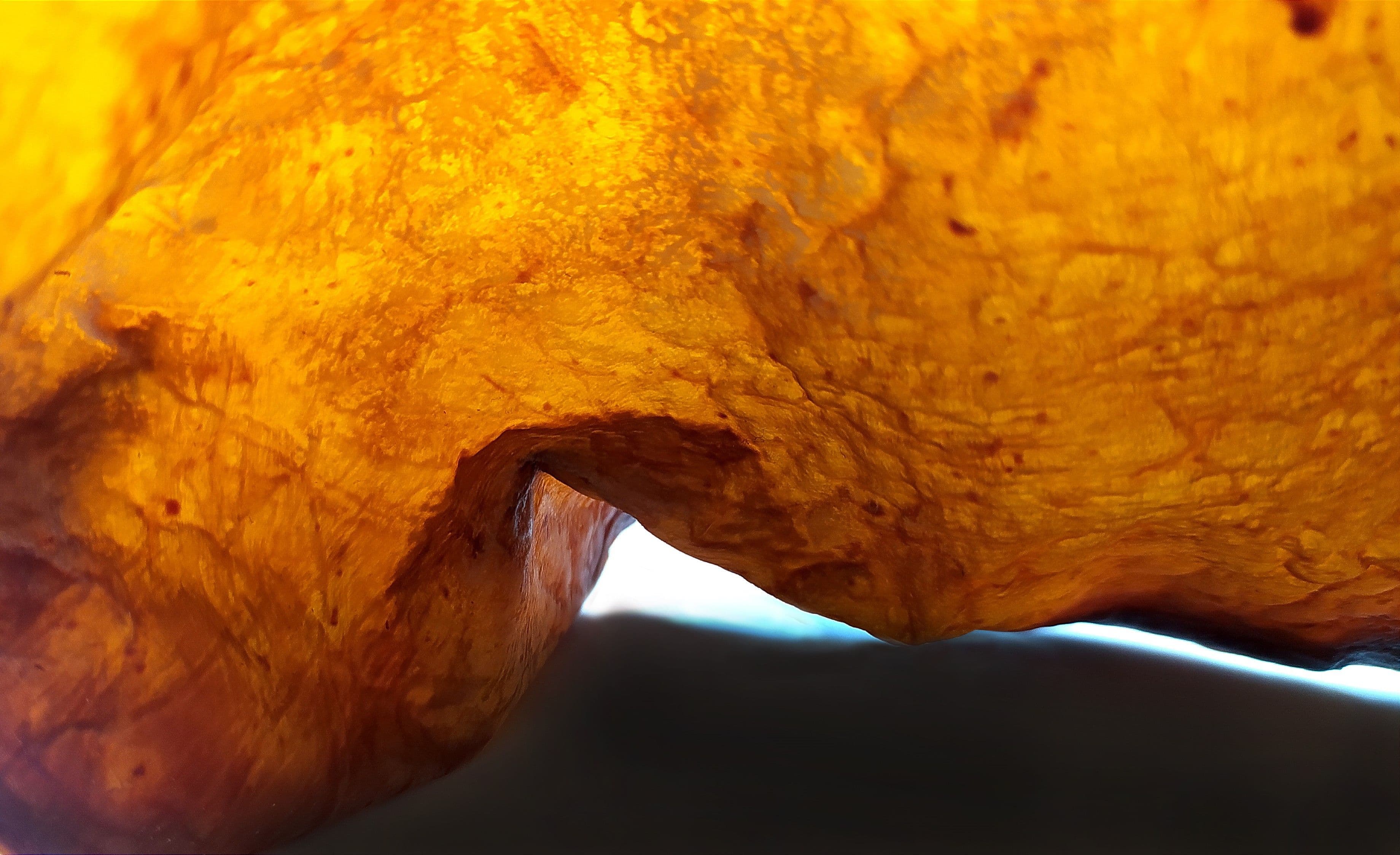

For example, “Uterine Spaces”, a conceptual work developed in the early months of 2023, is inspired by the nurturing qualities of the uterus and aims to link architectural space to life, death, and the biodegradation of its materials. The main component of this space is in fact a biomaterial obtained through the fermentation of a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast called SCOBY.

The images connected to “Uterine Spaces” showcase environments that seem to pulsate and foster the exploration of a space that is no longer inert and inorganic but can transform and biodegrade over time, finally becoming compost that will nurture the earth in a positive feedback loop.

Could you share insights into the challenges and opportunities you've encountered while conducting hands-on experimentation with biomaterials?

A fundamental step for me was to put my theoretical research into practice. Biofabrication has allowed me to "get my hands dirty", using a transdisciplinary approach that aims to support the exploratory and creative dimension of design, while promoting "material activism".

This method of self-producing materials is significant as it empowers designers to spearhead the development of new materials to attain the desired characteristics and stimulate our active, creative force to support a long-term positive future. To do so, open-source recipes and low-tech tools are employed for conducting in-house material experiments. Through testing various concentrations of bio-based components, new insights arise as the final material evolves and takes shape.

On the other hand, among the challenges encountered, the use of biological materials, when not in a controlled environment, could generate unforeseen circumstances related to deterioration or colonisation by molds and pests, due to non-optimal working conditions.

Nevertheless, this could represent a means to overcome the anthropocentric desire to always be in control and go beyond human mastery. Deconstructing humans’ role of superiority over other species is important to finally embrace non-human organisms as co-designers in the whole process.

What advice would you give to emerging designers and architects interested in integrating biotechnological strategies into their work?

To understand but, above all, address the complexity of the environmental challenges that are currently affecting the planet, I believe it is necessary to adopt innovative approaches that overcome traditional disciplinary barriers.

In response to these challenges, it is fundamental to integrate knowledge and perspectives from different domains, providing a conceptual and operational framework to support the design of more sustainable and resilient environments. A strong transformative potential emerges precisely when we embrace diversity, transdisciplinarity, and intersectionality and we give priority to that kind of "ecological" consciousness that challenges binary divisions to deconstruct traditional architectural narratives.

I, therefore, suggest young designers break all the barriers and adopt a systemic approach that redefines the notion of dwelling as a space for dialogue and coexistence among multiple species. “Human scale” can no longer be a valid concept in a present that requires an adequate and interspecific response to global problems.