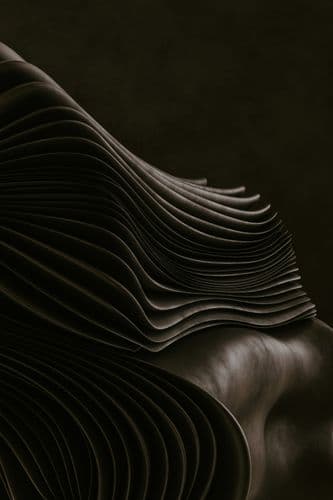

1. Your project explores the potential of paper as a valuable resource rather than just disposable material. Could you explain how this shift in perception was central to your design process and how it influenced your material choices?

Yes, reframing paper from something disposable to something durable and precious was foundational to my project. I wanted to challenge the common perception of paper as ephemeral and cheap. By focusing on discarded materials like paper bags, I began to see potential in what others overlook. This shift not only guided my material choices but also deepened my respect for paper’s inherent qualities—its strength, texture, and ability to age gracefully. It became important for me to preserve and enhance these traits, using processes that celebrated paper's imperfections and history.

2. You incorporated both traditional Japanese craft techniques and modern technologies, like laser cutting, in your work. How did these two approaches complement each other in enhancing the paper's value and functionality?

Combining traditional Japanese techniques with modern technology has become a natural progression in my practice. Drawing inspiration from Kakishibu dyeing (fermented persimmon tannin) and Katagami stencils (Washi paper coated with Kakishibu), I focus on revealing the organic strength and beauty of paper. In contrast, laser cutting allows me to explore new levels of precision and intricacy. Rather than opposing each other, these approaches complement and complete one another. Traditional methods bring depth, tactility, and durability, while digital tools offer expanded design possibilities and scalability.

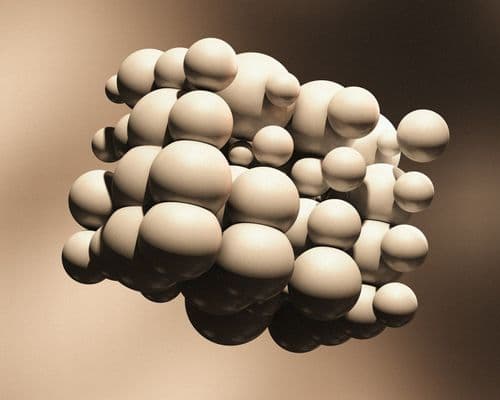

3. In your project, you’ve focused on regenerating paper waste, especially paper bags, to create high-quality artworks. What specific properties of paper bags did you find most intriguing when exploring their potential for upcycling?

What intrigued me most about paper bags was their durability and the way they record usage through creases, stains, and textures. These marks of use became part of the narrative embedded in each artwork. Used paper bags have a tactile memory and identity—remnants of our consumption. Some are made of surprisingly high-quality pulp and can endure treatments like embossing. This resilience, combined with their humble origin, made them ideal for transforming into refined sculptural pieces while maintaining a trace of their past life.

4. Your work combines natural painting with modern design techniques. Could you walk us through the technical considerations behind this integration and how you ensure the longevity of the paper artworks created?

Longevity is always a main interest of mine, especially when working with a material traditionally seen as fragile. I use Kakishibu, a natural dye derived from fermented persimmon tannin, which not only gives a warm, rich tone but also waterproofs, repels insects, and strengthens the paper over time. Technically, I test how the paper responds to different coatings, folding, and cutting processes. Modern techniques like laser cutting are calibrated to avoid burning or weakening the material. The goal is to enhance visual appeal while maintaining or improving the paper’s integrity.

5. The relationship between nature and craftsmanship seems central to your work. Can you elaborate on how the Japanese traditional techniques used in your project honor the natural properties of paper and elevate its role in modern design?

Japanese techniques like Kakishibu and Washi paper-making are deeply respectful of natural cycles and materials. They don’t seek to overpower the medium but instead work in harmony with it. By embracing this philosophy, I let the paper’s grain, weight, and texture guide the design. These methods slow down the process, inviting reflection and connection. In a fast-paced, mass-produced world, this sense of reverence elevates paper into a central character in design.

6. In your opinion, how can upcycling techniques such as those you used in this project be applied to other materials commonly discarded or overlooked, and how do you see this influencing future sustainable design practices?

I believe thoughtful upcycling can be extended to almost any material—whether textiles, plastics, or metals—as long as we approach each with curiosity and respect. The key is understanding the full life cycle and inherent value of each material, rather than viewing it as disposable. Designers need to move away from the “make-use-dispose” model and instead foster a culture of transformation, mending, and reuse. Embracing this mindset will shape more sustainable design practices in the future.

7. Your project suggests that paper, often seen as disposable, has significant artistic and functional potential. How do you hope this shift in thinking influences consumer behavior and the broader design industry, particularly in relation to sustainable consumption?

By revealing the strength, beauty, and versatility of paper, my project questions the idea that paper is a throwaway material. I hope to encourage consumers to value not just the final product, but also the material, process, and labor behind it. When people develop a deeper connection with materials, they are more likely to consume mindfully and treat objects with care. For the design industry, this shift can lead to more responsible, meaningful practices focused on material possibility and cultural context rather than trends or convenience.

8. Working with both the tactile quality of paper and the precision of technology must have presented some unique challenges. Could you share some of the technical challenges you faced and how you overcame them in the process of turning paper waste into functional artworks?

There were many unexpected challenges. Laser cutting, for instance, can easily scorch paper, especially with inconsistent densities or uneven surfaces. I had to experiment with power settings and speeds to preserve detail without damage. Another hurdle was reinforcing the structural integrity of folded or layered forms. I addressed this through traditional coating techniques, and sometimes by folding and stitching. It was a process of trial, error, and patience, always returning to the material to understand its limitations and possibilities.

9. Looking forward, how do you envision the future of materials like paper in sustainable design? Do you see the potential for broader applications in high-end design?

I see paper as a viable and sustainable material for architecture, product design, and interiors. With the right treatments and innovations, it can be strong, beautiful, and highly adaptable. In high-end design, where story, process, and authenticity are valued, paper has the potential to shine—not as a substitute, but as a centerpiece. I hope to continue pushing its boundaries and collaborate with others to redefine luxury and craftsmanship in a sustainable future.