Key Points

- Most early-stage “green” materials fail on the line, not in the studio; the bar is consistency over ~100,000 production cycles, not a single elegant prototype.

- “Recyclable” is a claim, not a measured property; one supplier demonstrated re-processing a recycled grade up to 15 times.

- Near-term beachheads: appliance housings with minimal electronics, interior panels and finishes, and functional textiles; complex electronics and safety-critical auto parts remain hard.

---------

Highlights of Tocco team discussion with Sofia Chaintouti

Before a mushroom-based “leather” becomes a hotel chair, it has to survive the furnace. That line, both literal and metaphorical, runs through Sofia Chaintouti’s career.

Over more than a decade at DuPont and Dyson, she worked as a materials engineer and later a team lead bridging design idealism and industrial realism - moving from conductive solar inks in her DuPont days to circular polymers at Dyson. The job description could fit on a label: take a sketch with lofty intent and reverse-engineer a materials stack that meets aesthetic, mechanical, environmental and economic constraints at volume, on deadline. Or, as she puts it: “Sometimes it felt like catalogue shopping, sure, but often we were writing the catalogues ourselves.”

The gap between a design-week promise and a stable production run is where many plant-based and recycled materials stall. “Some of the most beautiful and sustainable materials I tested couldn’t handle industrial moulding. They disintegrated.” Contract manufacturers are rational: variability is margin leakage. A composite that burns unevenly or flows unpredictably can push scrap toward 20% - a non-starter. Surviving the line means tolerating heat, pressure, tool wear and real factory variance for roughly 100,000 cycles, all while clearing regulatory compliance. Prototypes do not face that gantlet; mass production does.

Language adds to the confusion. “A lot of materials are recycled. Very few can be recycled again.” The fix is to separate properties (measured), attributes (described) and claims (marketed). “Recyclable is not a property. It’s a promise, and often a broken one.”

The practical benchmark is repeatability. Chaintouti points to one supplier that demonstrated re-processing up to 15 cycles—evidence of infrastructure thinking rather than checkbox thinking.

Where does adoption move now, without the fairy dust? Start with simpler bills of materials. Household appliances that lack complex electronics qualify faster because fewer flame-retardancy and heat-management constraints apply. Interior products - panels, furnishings, wall finishes - offer high aesthetic payoff against a manageable compliance bar. Functional textiles, including recycled and technical blends, show momentum: not a stampede, but movement. Electronics remain “still very hard.” In cars, interior trims are feasible; safety-critical components remain for “the brave few.”

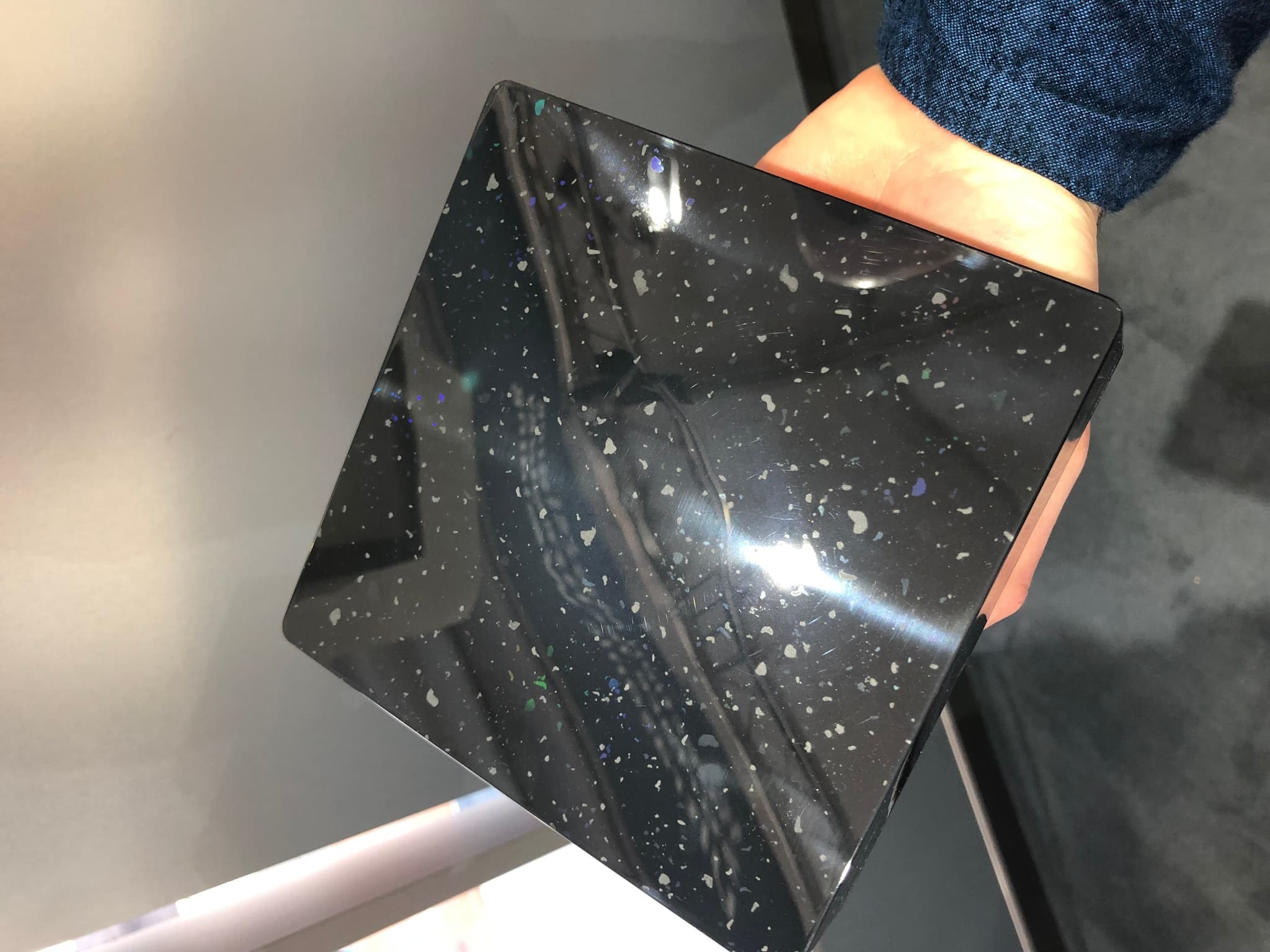

Perception is also a product of process. Recycled polymers are not condemned to a matte, second-class finish. Chaintouti points to a K-Fair demonstration where induction-based mould heating improved gloss and surface quality, narrowing a persistent aesthetic gap with virgin resins. In other words, a process window can move a market window.

The plastics question demands adult supervision rather than ritual denunciation. “I used to hate plastic. Now I respect it… It’s one of the most performant materials ever invented. We couldn’t live without it now.” The task is contextual management: pair polymers “with smarter design systems,” deploy them where they shine, and accept that some grades are stubbornly hard to recycle. That implies designing end-of-life from day one—collection, reuse and re-processing included - rather than gesturing at circularity later.

Markets don’t buy datasheets alone; they buy stories, signals and status. “One person’s innovation is another’s compromise.” In European luxury, “vegan leather” can read as virtue; in China, the same pitch is often rejected as down-market. For a material strategy to travel, it must be tuned as carefully to culture as it is to compliance.

The most common failure mode is inventing a hammer in search of nails. To Sofia, start with the nail: thermal envelope, load cycles, chemical exposure, lifespan. Then formulate to the target. “Fungi-based foam sounds great. But what’s it for? What temperature will it face? What lifespan does it need?”

If there is a missing piece, it is usable infrastructure - the boring software and data hygiene that turn one-off heroics into repeatable choices. “If I had a tool that mapped real-time material trends by region, sector, cost range, I’d have used it every day.” Internal libraries tend to decay under taxonomy drift, inconsistent records and poor UX. The request is specific: “A platform that distinguishes between claims and properties… that connects suppliers and designers with clarity. Not a database, a dialogue.” It is an engineer’s wish list for a market still dominated by PDFs, pitches and mythology.

None of this requires miracles. It requires systems: qualification protocols that reflect line reality; language that separates what is measured from what is marketed; process controls that close perception gaps; and tools that help non-experts navigate the mess without romanticising it. Chaintouti’s concluding line is not a slogan so much as an operating rule: “We don’t need miracles. We need systems that let the good ideas survive contact with reality.”

The consequence for anyone building with bio-based, recycled or hybrid materials is clear. Treat the factory as the filter and the data as the guardrail. Test for 100,000-cycle realities rather than single-shot charm. Prove repeatability, not just recyclability. Tune the market story to the audience you are actually selling to, not the one you hope to impress. And do the unglamorous work of specifying the nail before inventing the hammer. That is how green claims become shipped products rather than mood boards.