1. Your MUTATION OF THAI HANDCRAFT project blurs the lines between science, art, and engineering. How do you approach integrating natural, regenerative materials within this multidisciplinary framework while ensuring sustainability remains central to your work?

This project was developed during my BA in Product Design at Silpakorn University in Thailand, where I started noticing how traditional Thai handicrafts and materials were being forgotten. At the same time, I observed how modern manufacturing processes were replacing handmade items—such as baskets and trays—with mass-produced alternatives. This shift is not only technical but also cultural, as it sidelines human knowledge and wisdom embedded in craft.

My approach focuses on bridging the gap between technology and traditional craftsmanship. While sustainability in craft is often already inherent—through the use of local, natural, and low-impact materials—I also view sustainability as supporting the survival of the community of knowledge that sustains these practices. In this project, technology becomes a tool not to replace, but to empower, extend, and mutate craft traditions into contemporary relevance.

2. In your project, you emphasize avoiding synthetic chemicals and focusing on renewable materials. Can you explain how you select these materials and ensure they meet both your aesthetic and sustainability criteria?

For this project, I revisited the material roots of Thai craftsmanship. Before the introduction of synthetic chemicals, artisans used natural substances like tree-derived lacquer to waterproof woven baskets—a practice shared across Asia, including Japan. This historical wisdom guided my material selection.

I focus on materials that align with both ecological responsibility and aesthetic richness. Each item in the homeware collection is an outcome of that thinking—where design decisions are informed by both functionality and the cultural context of traditional Thai techniques.

3. What role does biomimicry play in your designs, especially considering the natural regeneration of materials, and how do you see this influencing future material applications?

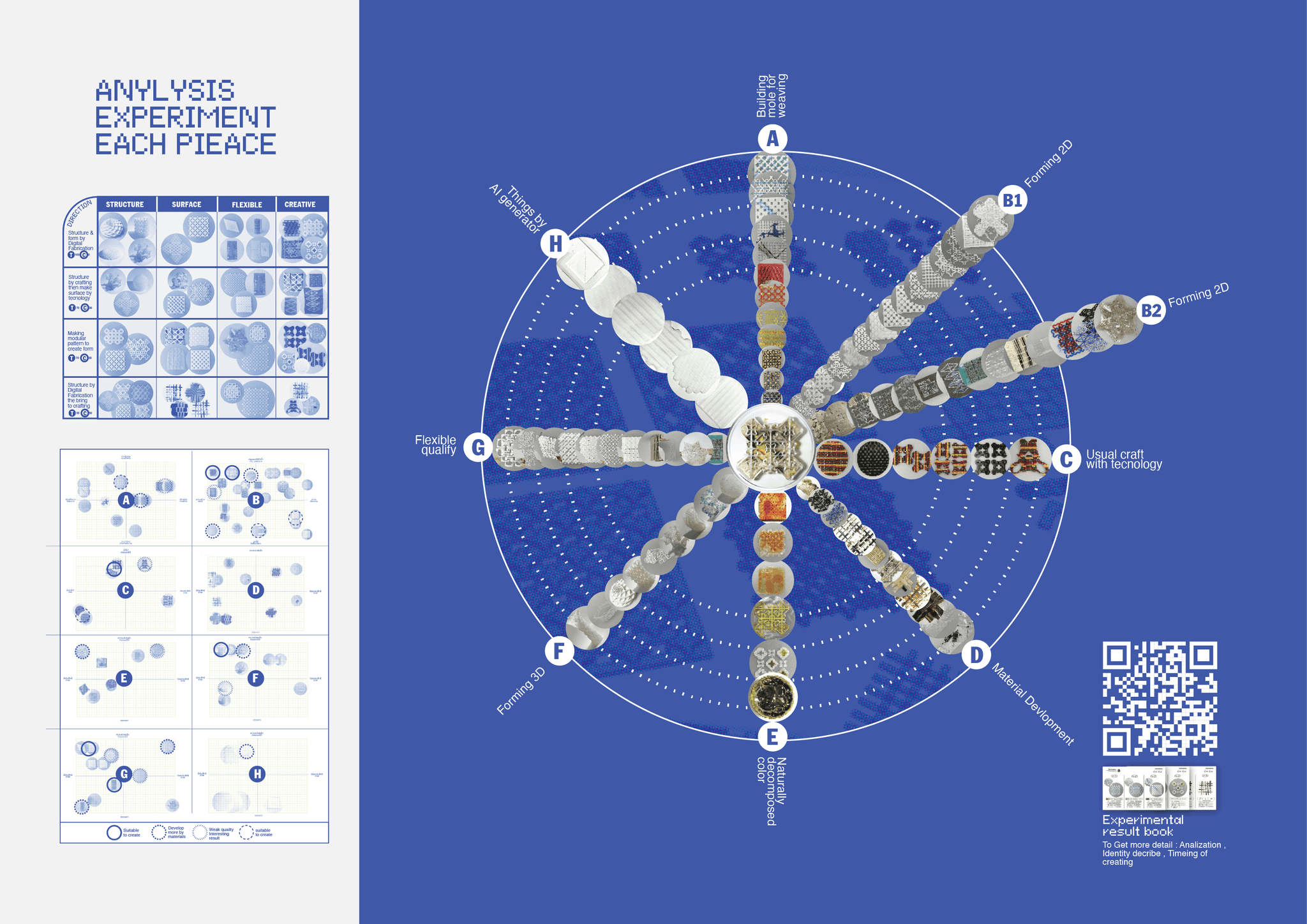

While I didn’t consciously use the term biomimicry at the time, the concept deeply shaped the project's thinking. I was inspired by cellular mutation—the way some cells must adapt under environmental pressure in order to survive. Similarly, Thai craftsmanship wasn’t in a position to evolve on its own within a modern, tech-centric design landscape. It needed a “catalyst”—in this case, technology—to mutate and adapt.

Each design in the collection reflects different stages of cellular mutation—from prophase to meiosis—translated into the forms and weaving structures. This metaphor offers a biological narrative for cultural adaptation, emphasizing evolution through resilience.

4. How do you ensure the materials you use for your Thai handcraft mutations are both ecologically responsible and technically suitable for the product’s functional needs?

Each product in the collection has a defined lifespan—some are designed for long-term use, others are intentionally degradable. I balance the ratio of traditional craft and technology in each piece to meet functional requirements.

For example, when the craft element dominates, the product might naturally degrade faster, reflecting its life cycle. I also ensure all dyes are ecologically responsible—such as using Terminalia catappa to dye bamboo into a unique neon green, reconnecting to the roots of Thai craftsmanship.

5. Sustainability often calls for a balance between innovation and practicality. In the context of the MUTATION OF THAI HANDCRAFT, what have been your biggest challenges in developing new materials that are both eco-conscious and commercially viable?

The main challenge lies in working with two very different communities—craftspeople and technology technicians. Artisans often carry long-standing cultural wisdom that may not easily align with experimental or modern approaches. At the beginning, there was resistance.

But through direct engagement, prototyping, and showing respect for their practices, I was able to communicate that my goal wasn’t to change their identity—but to preserve and extend it. Each region in Thailand has unique materials and wisdom, which I treat as the foundation—not an obstacle—for commercially viable material design.

6. Your project focuses on nature-driven solutions. How do you ensure the materials used are not only sustainable but also scalable for broader design and production processes?

Traditional Thai craft is inherently sustainable—it doesn’t rely on chemicals or destructive practices. The challenge isn’t ecological, but scalability. To address this, I introduce technologies such as laser cutting and 3D printing to support parts of the process—enhancing efficiency without compromising the heart of craftsmanship.

However, I believe not everything needs to be scaled. Craft is about time, care, and connection. Scaling should always respect the community's capacity, avoiding the risk of technology replacing the human hand.

7. With a growing emphasis on regenerative design, how do you envision your work with natural materials like plant-based fibers and organic dyes evolving over the next decade?

Instead of thinking of this as evolution, I see it as a return. We’re not inventing something new—we’re going back to the roots. Plant-based fibers and organic dyes were already in use before synthetic ones took over. Every region had its own methods, its own biodiversity.

The future of material design lies in refining these traditional methods using contemporary tools—technology, science, engineering—to make them more precise, adaptable, and widely appreciated. Ideally, industries will shift from using nature as a resource to working with nature as a collaborator.

8. How does working with traditional Thai materials influence your overall design process? Are there any particular cultural considerations that guide the way you approach material innovation?

Absolutely. Traditional Thai materials aren’t just resources—they’re reflections of regional identities. Thailand sits at a cultural crossroads, with overlapping influences from Myanmar, Laos, Malaysia, and more.

Each region’s craft traditions are shaped by their local ecosystems—water scarcity in the northeast leads to water-storage solutions, while heavy rainfall in the south demands water-resistant materials like lacquer. This context shapes how I design. Material innovation must start with location—its challenges, climate, culture—and build from there.

9. The project seems to blend a rich history of craftsmanship with forward-thinking material science. How do you educate and engage your collaborators (e.g., artisans, designers, engineers) to ensure they are as invested in the sustainable material process as you are?

At the time, I was in my early twenties—very young to be leading conversations with experienced artisans and engineers. So I started by experimenting and prototyping on my own. Then I shared samples and ideas with artisans, letting them interact with the outcomes before explaining the technical side.

This approach worked. By experiencing the material firsthand, they became curious, engaged, and eventually open to deeper collaboration. I avoid overwhelming them with jargon—instead, I let the material and form speak first.

For me, sustainability isn’t just about material—it’s also about cultural preservation. I see technology as a language to encode traditional wisdom into new forms, ensuring Thai craftsmanship continues to evolve without losing its DNA.